December 1996 Three

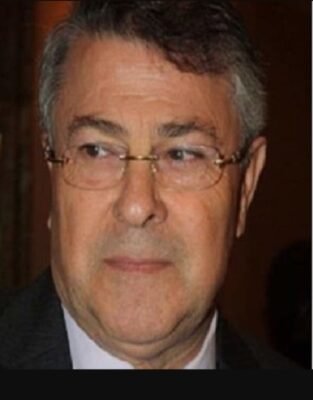

years ago, on 10 December 1993, Mansour Kikhia disappeared from his five-star hotel in central Cairo in Egypt. His family and friends have been without news ever since and no one seems to have any idea of what exactly happened to him. It took the Egyptian Government a full week before acknowledging the abduction. General Al-Alfi, the Minister of the interior, recognized the disappearance of M. Kikhia on 16 December

, at a press conference and affirmed that his Ministry would do everything to find M. Kikhia , determine the circumstances of his disappearance and identify his abductors. He refused, however, to give any further details, on the pretext that this might be detrimental to the ongoing investigation, on the circumstances of the abduction or on the way the Egyptian Government intended to pursue its investigations to find M. Kikhia, despite pressing questions from reporters. That same tendency to impose a real black-out on what we have to call the “Kikhia’s Affair†is still prevailing. In reply to an inquiry from the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance of the UN Commission on Human Rights on the progress so far made in the “Kikhia’s Affairâ€, the Egyptian Government has recently submitted a memorandum, dated 13 August 1996, reaffirming its previous position that there was nothing further to report, but adding, and this is new, that M. Kikhia came to Cairo “to attend a meeting organized by a non-governmental organization that did not request any special protection for M. Kikhia nor did it inform the authorities that his life was in dangerâ€. Should we therefore conclude that the Egyptian Government bears no responsibility for the abduction in Cairo of M. Kikhia or, on the contrary, should we regard its position as an attempt to cover up this “affair†and to hush up its serious international and domestic political consequences? Before concluding anything let’s start from the beginning. First, one has to be aware that M. Kikhia was not a common or ordinary visitor. He was a former minister for Foreign Affairs of Libya who was once well known and even appreciated in Egypt for his pan-Arab and sometimes openly pro-Egyptian political positions. He still kept a solid friendship with several Egyptian personalities including Foreign Minister Amr Moussa, the Arab League Secretary-General Ismat Abdel Meguid and M. Nabil al-Araby, Egypt’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations. It was, in fact, his commitment to pan-Arabism that militated in favour of his appointment, in 1972, as Libya’s Minister of Foreign Affairs following the signing of the treaty to uniting Libya and Egypt, better known as the Benghazi Declaration signed on 30 March 1971 by Presidents Sadat and Qaddhafi. The Government of President Mubarak did not hesitate to issue a special authorization in 1987, in the aftermath of his rupture with President Kaddafi’s politics, to open an office for M. Kashia’s opposition movement, the National Alliance (Al-Tahaluf Al-Watani) consisting of nine political parties and groups opposed to President Qadhafi. The office of this movement was closed only after the resumption, in 1989, of normal diplomatic relations between Egypt and Libya. M. Kikhia was subsequently informed politely that his presence in Egypt was no longer desirable. He did not return until 29 November 1993 when the Egyptian Government, at the request of the Arab Organization for Human Rights (AOHR) whose headquarters is at Cairo, reluctantly granted him a visa to attend the General Assembly of AOHR of which M. Kikhia was a member of the Board of Trustees. Problems linked to M. Kashia’s entry into Egypt again surfaced at Cairo Airport where the police did not seem aware of the visa granted to M. Kikhia whose name, one may presume, was still listed in the “persona non-grata†register. This probably explains the three-hour questioning undergone by M. Kikhia in the airport security headquarters on the origin of his visa and on his political activities. Two additional hours of waiting were necessary before he was finally authorized to cross the airport doors. In Cairo, M. Kikhia stayed at Al-Safir hotel, the same place where the AOHR General assembly was to convene. The hotel security was tight and well organized as Ministers, Ambassadors and other VIPs, including the US Under-Secretary for Human Rights John Shattuck, participated in the General Assembly which lasted from 1 to 3 December 1993. It was a great success for AOHR, which viewed the Egyptian Government’s active participation in the meeting as virtual official recognition of the organization which Egypt had hitherto carefully avoided recognizing despite the fact that AOHR had established in 1983 its headquarters in Cairo. It was also a source of great satisfaction for Egypt which, by virtue of this meeting, found itself in the forefront of the Arab human rights movement at a time when its Government was accused by independent non-governmental human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, of serious human rights violations. These were, in short, the circumstances of M. Kashia’s disappearance. One has to add, to complete the picture, that neither his family nor the Egyptian Government has ever received any demand for ransom and nothing has been found to indicate that M. Kikhia may have been killed. What is sure therefore is that M. Kikhia was not a victim of foul play. His disappearance was of a political nature and could only have been decided on political grounds. It is therefore clear that the search for the abductors and their sponsors should be oriented towards those who perceived M. Kikhia as a serious political opponent and a dangerous alternative to their control of power. In fact only the “Revolutionary Committees†of Libya could have this perception as they refuse, for fear of loosing power, the very principle of opposition however pacific and democratic it may be. For the Libyan Government “the revolution has only unconditional soldiers and natural enemiesâ€. It is feared that M. Kikhia may have been put into the category of “natural enemies of the revolution†and he may therefore have been subjected directly to the law of “physical liquidations†like the dozens of Libyans who have been assassinated all over the world or indirectly through an enforced and permanent disappearance as in the cases of Imam Moussa al-Sadr and his two companions who vanished in Libya 19 years ago and the two Libyan opponents Jaballah Matar and Izzat al-Mugaryaf who likewise disappeared in Egypt in March 1990. But did M. Kikhia really exhibit the characteristics of a “natural enemy of the revolutionâ€? M. Kashia’s association with the present Libyan regime began in the aftermath of the violent military coup d’彋at carried out, on 1 September 1969, against the civilian Government of the old King Idriss. While he was heading the Libyan delegation to the United Nations in New York, the new regime recalled him, on 7 September 1969, and offered him the prestigious post of Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs. He was then entrusted with the most important and most sensitive file, namely the preparation of a strategy for new relations with the United States of America based on two essential elements, evacuation of the US Wheelus Field air base near Tripoli and a review of the oil pricing system. He led the negotiations with the Americans that ended, on 11 June 1970, with the evacuation of the US troops from Libya. This first success, added to the special talents of M. Kikhia (who was well known to be a subtle, intelligent and cultured diplomat) put him at the forefront of the national political stage especially since his superiors in the “Revolutionary Council†came from the military without diplomatic experience and with a modest intellectual level. Soon he was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs and it is here where he began to encounter serious difficulties. Firstly, and as a democrat, he disapproved the excesses of the “Cultural Revolution†that President Qadhafi launched in April 1973 from the city of Zwara and which resulted in brutal and effective suppression of all individual freedoms. Secondly, he was disheartened, as a man of law, by the extend of the violations of basic human rights. He ended up witnessing, helplessly, the imprisonment of hundreds of intellectuals including several of his friends who were accused of being counter-revolutionaries for reasons as simple and artificial as being found in possession of books or newspapers. A first split with the regime took place in 1974 when M. Kikhia resigned from his post of Minister for Foreign Affairs to devote himself, through his law firm, to the defence of political prisoners whose numbers kept on rising, particularly after the failure of the coup d’彋at organized and led, in August 1975, by Captain Omar al-Mahesh, perhaps the most cultured member of the Revolutionary Council and a close friend to M. Kikhia. It was only in 1977, following the election of Libya to a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council that the Libyan regime called again on M. Kikhia’s diplomatic ability by appointing him Permanent Representative of Libya to the United Nations. In New York M. Kikhia devoted most of his diplomatic activities in the Security Council and in the General Assembly to the Liberation movements particularly the struggles against apartheid in South Africa and Zimbabwe and against Zionism in Palestine. It was also an opportunity for him to re-establish contact with his exiled friends who had left the country as a result of the excess of violence generated by the so-called “Popular Revolution†of 1976 which led to random assassinations and mass arrests, particularly among the ranks of intellectuals and students. The final split with the regime was not far away as the country continued to sink into endless settlements of accounts characterized by the establishment, by the newly established “Revolutionary Committeesâ€, of revolutionary courts in schools and universities that sent a score of innocent citizens to the gallows. The execution in March 1980 of attorneys Amer Al-Dughais and Mohammed Himmy, two close friends of M. Kikhia, finally convinced him that there was nothing more to expect from a regime that increasingly confused chaos and revolution, violence and democracy. On 18 September 1980, he resigned from his post as Permanent Representative to the UN. A new page was opened, a page that would lead to his disappearance on 10 December 1993 in Cairo, Egypt. M. Kikhia began his open but always non-violent opposition to the regime at Tripoli by advocating the same themes and ideas as those he used to promote even when he was a Minister namely the need to establish in Libya a truly democratic State based on the separation of powers, including an independent judiciary and endowed with stable institutions freely chosen in periodical free and fair elections. For him, political alternation and transparency were essential political elements as they guaranteed the continuation of the democratic process by discouraging and deterring any dictatorial impulses. All this should be accomplished through political dialogue and without resorting to violence or foreign countries, that is to say non-Arab powers. It is not difficult to imagine the cool reception the Libyan opposition movement reserved for such analyses at a time when President Reagan was busy preparing his war against the regime at Tripoli. The first meetings with leaders of the opposition such as M. Mohammed al-Migaryaf, Secretary General of the Libyan National Salvation Front (by far the most important opposition group at that time), were , to say the least, hardly encouraging for M. Kikhia who realized that his strategy did not fit in with the hard-line position of those opponents who preceded him. Those who were familiar with M. Kikhia knew that he was not the kind of person who was easily discouraged or distracted by initial complications or difficulties. Hence, his first disappointments provided him with new energy that allowed him to direct his contacts everywhere and in all directions. Firstly he re-established links with pan-Arab non-governmental organizations. The Union of Arab Lawyers, presided over by a lawyer and a former Minister for Foreign Affairs of Sudan, the Centre for Arab Unity Studies and its branch the Congress of the Arab People, the Union of Arab Jurists, the Arab Organization for Human Rights and others of lesser importance , which were all originally pro-Libyan, ( thanks to the diplomacy of M. Kikhia, founder or active member in most pan-Arab. organizations) and a source of pride to Libya, gradually distanced themselves from the Libyan Government and embraced the political discourse on Libya of one of their member, M. Kikhia. M. Kashia’s increasing activities were not, of course, to please Tripoli’s liking particularly since its representatives in several pan-Arab meetings were often faced with embarrassing situations in which they found themselves compelled to comment publicly on M. Kashia’s interventions. These were in no way forgiven to M. Kikhia, and it would perhaps be useful, for the Egyptian investigators to check this aspect to see if the fact of using the same turf as the Libyan Government did not finally irritate the latter to the point where it would do anything and everything to get rid of an increasingly burdensome opponent. In fact, it was certainly intolerable for a Government that pretended to represent the “Unity of the Arab People†to see its credibility crumble and dwindle day after day among its own “allies and friends†whose aspirations it claimed to represent. The success on “the Arab front†was to have two important consequences for M. Kashia’s political future. On one hand, the Arab success gave him a new momentum by showing that if he could succeed with his “Arab brothersâ€, there was nothing to prevent his success on the Libyan front. On the other hand, the Libyan opposition, realizing the political abilities and achievements of M. Kikhia and the magnitude of his public relations, henceforth became more attentive to his messages, approaches and moves. The opposition, in particular the left, embraced his strategy for the establishment of a democratic State in Libya. In 1977, no less than nine movements and political parties elected him to the post of Secretary General of a new political organization, AL-TAHALUF Al- WATANI. In April 1992, M. Kikhia signed an understanding of cooperation with M. Mugaryaf, the Secretary-General of the Libyan National Salvation Front, the largest group, at that time, of the Libyan opposition in exile. Thus, M. Kikhia completed the first phase of his strategy consisting in uniting the Libyan opposition around realistic objectives and a united leadership capable of convincing the Libyan Government to recognize the opposition and subsequently to negotiate with it, on an equal footing, the future of the country. All this made of M. Kikhia a leader of the utmost importance within the ranks of the Libyan opposition abroad if not simply the leader. In any case, the world perceived him as such. Even the Libyan Government was very alert to M. Kashia’s efficient leadership and his increasing political weight among Libyans and friendly Governments alike. This probably explains the continuous comings and goings of Libyan emissaries with all kinds of proposals to convince M. Kikhia to put an end to his political activities and to return to Libya where, according to the messages they carried,â€everything was possibleâ€. The proposals became more precise in the aftermath of the semi-official visit that M. Kikhia paid to Algeria on 7 October 1993 along with M. Al-Mugaryaf and a former member of the Revolutionary Council M. al-Houni following an invitation from the Algerian President Ali Alkafi, a personal friend of M. Kikhia and a former Ambassador of Algeria to Libya at the time when M. Kikhia was Libya’s Minister for Foreign Affairs. There is no doubt that this visit played a determining role in the decision to physically eliminate M. Kikhia. In fact the Libyan Government, which found itself isolated from what it considered to be its natural base, the pan-Arab movement and organizations, thanks to the quiet but efficient work of M. Kikhia…that government was fearful that another Kashia’s success, like the one he had just managed in Algeria, would increase its isolation. This was all the more worrying as M. Kikhia enjoyed respect and appreciation in several countries, including Tunisia, Jordan, Yemen, Iraq and even Egypt. Another factor that determined his elimination was, probably, the repeated mention of his name during the questioning of the military officers who led the Misrata Rebellion of October 1993. Despite all this, and as incredible as it may seem, the Egyptian Government affirms that no one has warned it that his life was in danger or that he was in need of special protection. This obviously evasive answer raises more questions than it answers. The first question is about the interrogation that M. Kikhia underwent in the airport and its relation to the threat that hung over him. In fact if the Egyptian Government was not aware that M. Kikhia was a “special visitorâ€, why question him for three hours, especially since he carried a visa issued in due and proper form. The visa itself should be the subject of several questions. For example, why was the visa issued only two days before the General Assembly that is to say on 28 November 1993, whereas M. Kikhia had requested it more than a month earlier through the Egyptian Embassy in Paris? Who authorized the visa and why were the police authorities in the airport not informed of that authorization? There is no doubt that serious answers to these and others questions may give momentum to the investigation on the disappearance of M. Kikhia. It could also save the Egyptian Government further embarrassment. For example, was the visa authorized to allow M. Kikhia to attend the meetings of the AOHR or was it simply meant to lure him into Egypt? It is to these questions that the investigators should seek clear-cut answers. Other questions could be based on those considered by the French investigators of the “Ben Barka Affair†of 1963, which is similar, in every detail, to the “Kikhia’s Affairâ€. In this context, the French Government did not await the end of the investigation to designate potential “beneficiaries†as possible sponsors of M. Ben Bark’s physical liquidation. The Government immediately arrested French and Moroccan security agents involved directly or indirectly in the abduction. Neither did France wait the end of the investigation to freeze its relations with the presumed sponsor country, Morocco. The Government of Charles De Gaulle even accused that country of having deliberately violated French sovereignty and threatened the security of the French people. International warrants were immediately issued for the arrest of General Mohammed Oufkir, the current Moroccan Minister of the Interior, and Colonel Ahmed Dlimi, Morocco’s top security chief. In the “Kikhia’s Affair†the Government of President Mubarak has not yet ordered any arrests. It has not even permitted the Public Prosecutor to question potential witnesses such as M. Hijazy, the Libyan Minister of the Interior, and M. Abdullah Al Senusi, The Libyan Deputy Chief of Security, both of whom happened to be in Cairo on the day of the abduction. It has not even been possible so far, due to the lack of cooperation on the part of the Egyptian security authorities, to question M. Yussuf Najm, the last person to meet M. Kikhia in his hotel in Cairo. The inertia in the “Kikhia’s Affair†seems to have attained such magnitude that M. Kashia’s lawyer, attorney Adel Amin, bluntly concluded, after commenting on and refuting the 13 August 1996 Egyptian Government response to the Commission on Human Rights, that everything “seems to indicate that the Egyptian security authorities do not wish the truth to be revealed concerning the disappearance of M. Mansour Kikhiaâ€. This conclusion of attorney Adel Amin is further substantiated by the growing special relationships that have been established between the Egyptian and Libyan Governments since, and perhaps because of, the abduction of M. Kikhia. This rebuts the score of analysts who logically predicted that relations between the two countries would experience serious difficulties as was the case between France and Morocco whose diplomatic relations were abruptly suspended and subsequently frozen as a result of the “Ben Barka Affair†with all its consequences for peace and war between the two powers. The harmony and understanding between Egypt and Libya in the post-Kashia’s era is such that a “special/extraordinary†minister has been appointed in each country solely to promote the special relationships between the two countries. In Egypt, for instance, the Libyan file falls within the exclusive competence of M. Safwat al-Sharif, the Egyptian Minister of information and a close friend of President Qadhafi. In Libya, it is M. Jumaa al-Fazzany, a Libyan of Ugandan origin, who is in charge of the Egyptian file at Tripoli. He is the only Libyan who, following the disappearance, declared that: “ Kikhia is not Libyan. He belongs to a feudal Turkish family that has nothing to do with the Libyan peopleâ€. Both Ministers of Foreign Affairs M. Moussa in Egypt, a friend of M. Kikhia, and M. Montasser in Libya, a relative of M. Kikhia, are thereby, effectively sidelined from the abduction file. On the economic front, since the disappearance of M. Kikhia the two countries have concluded several important cooperation agreements involving the investment of several million US dollars in Egypt. The many projects include the construction of Marsa Matrouh Airport, the Tobruk-Matruh railway and a Siwa- Al-Gaghbub road and the settlement in Libya of one million Egyptians and many other nebulous projects. In terms of direct investment in Egypt, according to a declaration made in Cairo on 1 July 1996 by M. Mohammed al-Howeij, the chief Libyan investment officer, since 1993, Libya has invested the sum of $440 Millions in Egypt. He added that “President Kaddafi’s directives are to double this amount in the next three years by repatriation, among other things, of Libyan assets in Europe evaluated at $290 millionsâ€. He concluded by saying those Libyan funds would be primarily invested into the public sector companiesâ€. It is noteworthy that a score of these companies should have been privatized long ago but their financial and productive situations were such that no one wanted to take them over even, in some cases, at a symbolic price (usually one Egyptian pound). This is, in short, the file on M. Kashia’s disappearance that clearly shows that the disappearance was, most probably, the result of a Libyan political decision to physically liquidate M. Kikhia after the failure to convince him, in a friendly or forceful manner, to put an end to his political activities which were perceived in Tripoli as an intolerable challenge. It is also clear that the Libyan regime would never have dared to undertake such a sensitive and dangerous enterprise without the formal or tacit consent of the highest political authorities in Egypt. This is all the more evident since Libya is under strict air embargo administered by the UN Security Council and for Libya, Egypt is one of only two main land communication corridors to the rest of the world, the second being Tunisia. Egypt is also a valuable mediator for Libya with Washington and London in the “Lockerbie Affairâ€. It is therefore clear that the price for Libya to go it alone would be too high and even prohibitive. In the present international context, it would be inconceivable for Libya to even think to embark on the slightest adventure against Egyptian interests, let alone its sovereignty. Under these circumstances, it is logical to think that, although planned in and by Libya, the abduction of M. Kikhia was certainly not carried out solely by Libyan agents. Egyptian complicity, at least technical and logistical, was necessary at one stage or another of the implementation of the abduction plan in order to ensure, at least, the protection of its ultra secret character from other Egyptian security services, which were not necessarily involved in the operation and to thereby minimize the risks of its leakage. The strategy seems to have worked perfectly until now. Everybody in Egypt, and even President Qadhafi, seldom misses an opportunity to declare that they have no idea of what happened to M. Kikhia whom no one has seen since 10 December 1993. This tactic of denying everything was probably learned from the case of Imam Mussa al-Sadr and his two companions who vanished in Tripoli on 30 August 1978. No one has seen them either. Another abduction case concerned two Libyan opponents, Al-Mugaryaf and Matar, whom no one has seen since they were taken from their respective home on 16 March 1990 by Egyptian official security agents to Egypt’s national security headquarters in Cairo. Evidence of any Egyptian complicity should be sought in the process of granting the visa to M. Kikhia, its issue date, and the person who authorized it. According to the present indications the date seems to have been chosen in such a way as to give M. Kikhia the least possible time in Egypt before the convening of the General assembly so that he would only be able to visit his uncle in Alexandria and his numerous relatives and fiends after the meeting. It would certainly have been much easier to put the abduction plan into effect after the return of the participants to their respective countries. To seize M. Kikhia before the meeting would have had several immediate and adverse effects on the image of the host country, including the possible cancellation of the General Assembly and the organization by the participants of protests in Cairo. The choice of the date of the kidnapping was not fortuitous either. It revealed the precise information available to the abductors, who waited the last minute before executing their plan. M. Kikhia was expected home in Paris less than 36 hours after his abduction on 10 December 1993 while the world was busy celebrating the 45th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Tareq Alnajjar 10 December 1996

المزيد من المواضيع

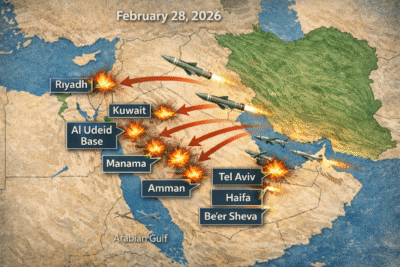

من حرب الخليج إلى لبنان واليمن وسوريا: حروب إيران وتصدير التوحش

بين القرار والمجتمع: لماذا أصبحت المراجعة ضرورةً سياسية؟

مدينة تؤازر إخوتها… الرقة